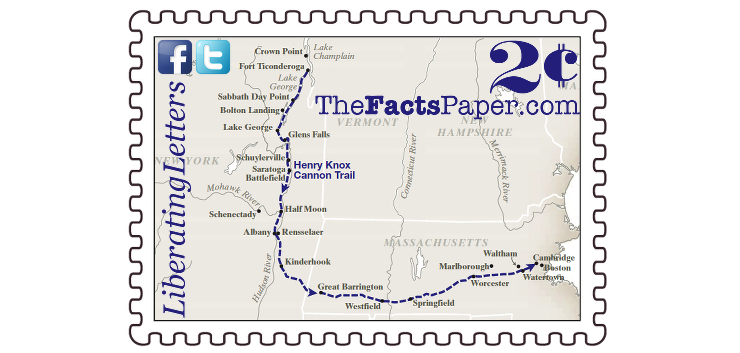

Henry’s “noble train of artillery” traveled eastward through Massachusetts unhindered, arriving in Cambridge on January 24, 1776. Washington ordered the guns to be strategically placed upon Dorchester Heights. Seeing the overwhelming firepower of the militia, the British chose retreat over attack and vacated the city on March 17, 1776. The Patriots entered Boston victorious the next day.

The expedition took 56 days in blistering winter weather, but the efforts of twenty-five year old Henry Knox and his men are credited as one of the most pivotal events of the American Revolution. Knox officially received his commission and rank of colonel upon his return from Fort Ticonderoga. He collaborated with Washington on several major battles, coordinating Washington’s famous Delaware crossing on December 25, 1776. (see Your Country Is At Stake) After the Battle of Trenton on the 26th, Knox orchestrated the return of the army, along with hundreds of prisoners and captured supplies, back across the river by that same afternoon. Because of his outstanding contributions to this successful mission, Knox was promoted to Brigadier General, made Chief of Artillery and given command of an artillery corps.

An icy storm set in as they boarded flat-bottom boats on the lake, threatening their mission. In a fight against time, the group pushed themselves to reach shore before the lake froze. The last boat arrived just as the water was beginning to freeze.

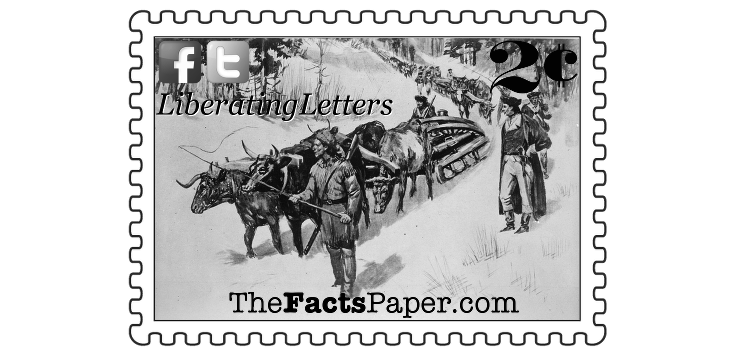

Once back at Fort George, Henry contacted a local farmer to “purchase or get made immediately 40 good strong sleds that will each be able to carry a long cannon … and likewise that you would procure oxen or horse as you shall judge most proper to drag them.” The sleds arrived in a few days and were promptly loaded with the weapons. Henry penned a note to Washington saying, "I have had made forty two exceedingly strong sleds & have provided eighty yoke of oxen to drag them as far as Springfield where I shall get fresh cattle to carry them to camp. . . . I hope in 16 or 17 days to be able to present your Excellency a noble train of artillery." The sleds needed snow to move, though, and there was none.

Henry and his men waited a week at the fort before Christmas morning brought the answer he desperately prayed for. God had been more than generous as several feet of snow covered their path making it difficult to cut through. But the men were thankful to be moving and pushed forward to Boston.

Taking almost two weeks just to reach Albany, Henry knew he would not make his predicted rendezvous with Washington. He set right to work analyzing if the Hudson was frozen enough to support the weight of the sleds and weapons. They attempted several times to cross, only to have two sleds break through the thin ice. On the third day, their luck turned around as they slowly but successfully guided 23 sleds across the frozen river. Citizens of Albany, who had become intrigued by the caravan, assisted the soldiers in retrieving the two sunken cannons. Unbelievably, no artillery was lost in the venture.

January 21, 2016

Dear Liberty,

Henry and his wife, Lucy, grabbed a few precious belongings on their midnight flight out of Boston. Since the night Henry watched the horrors of the Boston Massacre five years earlier, tensions between the British and the colonists had been escalating. (see Mayhem And Massacres) They reached the status of war after the Battles of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775. (see The Shot Heard 'Round The World) Henry and Lucy knew it was time to go. Henry’s in-laws, who were Boston Loyalists, tried to court him into the British Army but Henry had decided long ago where his allegiance lay.

Rushing out of town, they passed Henry’s bookstore, The London Bookstore, where he had studied and educated himself for the past four years on military history and science. It pained him to leave his valuable library behind but the British were coming. He needed to make sure his precious young bride was safe when he volunteered with the militia surrounding the city.

“Don’t fire until you see the whites of their eyes!” (see Defining The American Spirit) The warnings to preserve ammunition from Colonel Prescott rang in the ears of Henry and his fellow patriots as they prepared for the British attack on Breed’s Hill at Bunker Hill. Escaping the battle with his life, Henry set to work outlining better artillery locations around Boston. Even with stronger positioning, he knew they just didn’t have the necessary firepower to overthrow the British.

THE BOOKSTORE GENERAL

In September of 1780, Knox presided over the trial of a captured British Captain charged with being a spy, as well as participating in Benedict Arnold’s traitorous actions. Captain John Andre, the same British soldier Knox had shared a cabin with five years earlier, was found guilty and sentenced to hang by Knox and several other generals. (see A Tale Of Two Patriots)

As the war drew to a close in early 1783, Knox’s commission ran on a day-to-day basis. He remained active by designing plans for an organized peacetime military. It included two military academies, one each for the army and the navy. It also called for troops to secure the national boarders. Initially discarded by Congress, the plan eventually became the foundation of the United States Army. At this same time, Knox also established the Society of the Cincinnati, an organization for Revolutionary War officers. (see The Man Who Refused To Be King) It is the “oldest private patriotic organization in the United States,” as well as “our nation’s first hereditary organization.” Members entrusted their descendants with preserving the history, sacrifices and heroic actions of the patriots that gave America liberty.

Upon Washington’s retirement on December 23, 1783, Knox became the senior officer of the army until he resigned the following June. (see The Forgotten Holiday) Within a year, Congress appointed him to the vacated position of Continental States Secretary of War. Realizing the Articles of Confederation were proving to result in a weak national government, a Constitutional Convention was called in 1787. (see Constitution Day) After receiving an invitation, Washington wrote Knox for advice as to whether to attend. Knox positively responded saying, “It would be circumstance highly honorable to your fame, in the judgment of the present and future ages, and double entitle you to the glorious epithet — Father of Your Country.” Knox later sent Washington a preliminary design for a national government. The outline Congress eventually adopted was remarkably similar to Knox’s plan. (see The New Trinity)

With the development of an official War Department, Knox continued his position under the new title of United States Secretary of War. During his tenure, he oversaw the development of a regular national navy, a national militia, and the creation of coastal fortifications.

Knox retired on January 2, 1795, returning to his home, Montpelier, at Thomaston, Massachusetts (now Maine). He enjoyed time with his wife and children and dabbled in business ventures before his death on October 25, 1806.

Many don’t know the name Henry Knox nor what he did for the country. They do, however, recognize Knoxville, Tennessee, and Fort Knox in Kentucky, which houses the United States Bullion Depository, or "Gold Vault". These are just two of the many towns, counties, and sights across the country that bear his name in his honor. Henry Knox’s Trail, which follows the path of the “noble train of artillery”, extends through New York and Massachusetts and is denoted by road markers along the way. It is for the most part today’s Massachusetts Turnpike (Interstate 90).

Liberty, remember, we all have our part to play. Whether it’s bookstore owner or Brigadier General, this country is made up of people making their own contribution. Find your passion, find your strength, and then push yourself to excel in it. You never know where it may lead you. You never know how you might change the course of history.

That’s my 2 cents.

Love,

Mom

Henry recalled that back in May, militia leader Benedict Arnold, along with Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys, captured Fort Ticonderoga in the Providence of New York. (see A Tale Of Two Patriots) A large arsenal of artillery was left by the British, who deserted the fort without a fight. Arnold intended on bringing the military equipment to Boston, but eventually abandoned the idea and resigned his commission. Those firearms were just sitting in the fort and Henry knew it. The only problem was it was 300 miles away and winter was coming.

Knowing he had to move quickly, Henry rode to Cambridge to present an idea to his trusted friend General George Washington. He would travel to Fort Ticonderoga himself and retrieve the valuable weapons. With the heavy artillery, the Continental Army would have badly needed offensive support, allowing them the chance to force the British out of Boston. Using wagons and sleds, he predicted the expedition would take two weeks.

Henry was not a commissioned officer in the Continental Army but time was of the essence. Washington put Henry in charge of the campaign with the command "no trouble or expense must be spared to obtain them (weapons).” John Adams and others began working with the Second Continental Congress to commission him as colonel but Henry had to leave before the official appointment came through.

Briefly stopping in New York City for supplies, Henry set out with his brother, William, and a servant, Miller. They moved quickly to beat the temperamental weather, arriving at Fort George on December 4th. Having limited space, Henry shared a cabin for the evening with a British captive who was on his way to a prison camp. The two men had much in common including age, personality, and attitude. They spent the evening talking and sharing stories, enjoying the camaraderie and conversation. Henry bid the young man farewell as he left in the morning wondering what the future held for the young soldier.

Henry could see Fort Ticonderoga in the distance and started planning his next steps. Upon arrival, he carefully selected 59 pieces. On his list he noted 43 brass and iron cannons of various sizes, 8 mortars, 6 cohorns, and 2 howitzers. While the men at the fort dismantled the guns, Henry inspected the boats and ox carts that would take them down to Lake George.