May 13, 2017

Dear Liberty,

Robert wiped his brow before giving the signal to start the boilers. The sweat was not from the heat, but because of what he was about to do. Robert and the seven-man crew agreed, if they were caught, they would sink the boat. If they had to die, they would at least die free.

The crew went to work as Robert donned the captain’s signature wide-brimmed straw hat and jacket. Robert had studied Captain C.J. Rylea’s mannerisms for months. By wearing the captain’s things, he was convinced he could fool most anyone. Only allowed the title of "wheelmaster" as a slave, Robert had piloted the ship for years. Robert prayed it all was enough to take them to freedom. Even at age 23, his six years of experience on the Planter allowed him to be calm as he embarked on such a dangerous mission.

As usual, Captain C. J. Rylea broke military protocol, leaving the slave crew onboard while the three white officers went ashore to spent the night. Only one crewmember decided not to take the risk for freedom and left the ship before it departed.

As the Planter slowly pulled away from Charleston’s Southern Wharf, Robert casually glanced around at the roughly 20 guards placed across the wharf. Robert counted on the dark shadows of the night concealing his black skin underneath the captain’s attire.

The Planter contained five guns, including a howitzer and a pivot cannon, along with 200 rounds of ammunition. Since it was scheduled to leave in the morning to deliver much of that cargo to Fort Riley, the 2:00 am departure did not alarm anyone. However, as a precaution, they raised the Confederate Stars and Bars and the Palmetto flag knowing the ship’s commander, Brigadier General Roswell S. Ripley, would be notified immediately for any suspicious activity. (see How The South Was Won) Robert took one last glimpse of Ripley’s headquarters, located in view of the dock, never to look back again..

Robert steered the ship towards the nearby West Atlantic Wharf to pick up cargo even more precious than the guns. Waiting for the Planter was Robert’s wife and children, along with other crew family members and escaped slaves. After the quick stop, Robert settled into the pilot’s house as the ship started for the harbor.

The group was not free yet. They still need to safely pass several Confederate forts and batteries first. As they approached Fort Johnson, a God-fearing man, Robert looked to the sky and prayed, “Oh Lord, we entrust ourselves into thy hands.” He then gave the appropriate horn signal to request passage. Robert held his composer as he waited for what seemed like hours for the “Go ahead” response. Once given, he directed the ship onward.

By 4:00am, the Planter approached its last hurdle to freedom, Fort Sumter. (see Sibling Rivalry) Knowing guards at this checkpoint often boarded and inspected the ship, a few of the crew members approached Robert requesting to turn back. Trusting God would deliver them, he pressed on.

“Oh, Lord, we entrust ourselves into Thy hands. Like Thou didst for the Israelites in Egypt, please stand guard over us and guide us to our promised land of freedom.” After praying, Robert signaled the guards. Receiving the appropriate response, the escaped slaves quietly savored their first taste of freedom. As the ship sailed closer and closer to the Union blockade, each breath became more and more emboldening.

Once the Planter traveled out of Confederate cannon range, Robert instructed the southern flags be taken down. He collected the white bedsheet he told his wife to bring and raised it for the Union ships to see. Robert sent up another prayer that they would see it before firing.

“Open the ports,” ordered Acting Volunteer Lt. J. Frederick Nickels of the U.S.S. Onward. The rising sun revealed the oncoming Confederate ship to which the Union sailors readied their guns. They were quickly elevating a port gun until someone yelled out, “I see something that looks like a white flag.” Everyone stopped and stared at the ship. It was indeed a white flag.

The moment the passengers on the Planter realized they would not be fired upon, they began dancing and singing. Others cursed Fort Sumter, as she was now no longer a threat. Robert steered the ship up to the Union vessel. He removed his hat, greeting the commander, “Good morning, sir! I’ve brought you some of the old United States guns, sir!”

Robert promptly requested a United States flag, which he proudly raised on the ship that gave him and the others sweet freedom on May 13, 1862. Around the time General Ripley realized his prize ship was gone, Robert was turning it over to the Union commander, telling him, “I thought the Planter might be of some use to Uncle Abe.”

Escaped slave Robert Smalls quickly became a hero in the North. Not only did he deliver a valuable ship and cargo to the Union, he also gave them a captain’s code book, maps of laid mines and torpedoes, as well as personal, extensive knowledge of Charleston’s waterways and military configurations.

Personally invited by President Abraham Lincoln, Smalls and the crew visited Washington where they were acknowledged for their bravery. In addition, the heroes were each awarded a portion of the value of the Planter. Smalls met with Lincoln several times, including at least once with Frederick Douglass (see Reading, Writing, and Redemption) where the two activists convinced the president to allow black men to serve in the military. (see Doing Our Duty)

Smalls himself enlisted in the U.S. Navy and was assigned pilot of the Planter, now under the Union flag. In a battle on December 1, 1863, the ship’s captain ran from the pilothouse in fear. Knowing Confederates were ordered to kill captured black Union fighters, Smalls refused to surrender. He took command and saved the ship. This act of heroism earned him the rank of captain and assigned to the Planter, becoming the first black to command a U.S. ship.

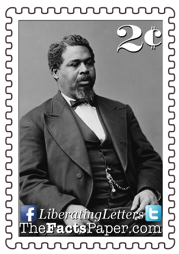

Smalls was born April 5, 1839, in Beaufort, South Carolina, to Lydia Polite, a slave of John McKee. Theories contend John, his son Henry, or the plantation manager, Patrick Smalls, was Smalls' father. Regardless, and probably because of, he was favored in the McKee household. Lydia worked in the house and she and her son experienced an easier life than other slaves. To open her son’s eyes, Lydia arranged to have her son sent to the fields to see the true horrors of slavery.

When he was 12, Lydia again arranged to have Smalls sent to the city to work, where he was able to keep a small amount of his earners. After having several jobs, at age 17 he discovered his true love in both vocation and life. He obtained a job on the Planter and also met Hannah, a slave working in a city hotel. The two were given permission to marry and live together in an apartment. (see Marriage Is What Brings Us Together Today) After their second child, Smalls realized his family could be taken from him at any time. At that point, he approached Hannah’s owner and requested to purchase her and the children. He was given the price of $800, an impossible amount for a slave who only had $100. He needed to find another way to find freedom for his family, which he did.

In October of 1862, prominent blacks in New York honored Smalls in a public reception at the church of Rev. Henry Highland Garnet. (see Call To Reason) As reported by The Evening Post,

Smalls was made an unofficial delegate at the Republican National Convention in 1864. Unfortunately, none of his accomplishments prevented Smalls from being asked to surrender his seat on a Philadelphia street car for a white person that same year. Ninety years before Rosa Parks made her “stand”, Smalls made his. (see Walking To Freedom) He chose to leave the car completely rather than ride in the open platform. Activists presented this shameful treatment of a heroic veteran in arguments that persuaded Pennsylvania legislatures to pass a bill desegregating public transportation in 1867.

After the war, Smalls returned to his boyhood home in Beaufort, and purchased it with his reward money. His mother lived with them as well. While in Philadelphia, an intelligent, but illiterate, Smalls spent nine months learning to read and write. Back in South Carolina, he organized a school board, started a school for black children and opened a store. He also entered politics.

In 1868, Smalls won a seat in the state’s House of Representatives, and then the United States House of Representatives in 1872. He also served as a delegate for several more elections. Smalls continued between state and federal positions for years, yet his political affiliation was never in question.

As Smalls wrote U.S. Senator Knute Nelson on August 22, 1912, "I never lose sight of the fact that had it not been for the Republican Party, I never would have been an office-holder of any kind—from 1862 to the present.”

In a September 12, 1912, letter, his description of Republican party coined it as "the party of Lincoln...which unshackled the necks of four million human beings". He ended that letter by asking, “that every colored man in the North who has a vote to cast, would cast that vote for the regular republican party and thus bury the democratic party so deep that there will not be seen even a bubble coming from the spot where the burial took place." (see The Birth Of A Movement)

Even after being instrumental in helping move racial equality forward after the Civil War, Smalls continued to experience racism and suppression by southern Democrats. Once Democrats regained control of South Carolina's state house, they began passing laws restricting black citizens' freedoms. (see Civil Rights...And Wrongs and Separate But Equal?) By redistricting their state, black representatives were forced out of their federal house positions. To finally get rid of Smalls, they falsely accused him of bribery. Some tactics never change.

Due to the racist actions of Democrat President Woodrow Wilson (see The Birth Of A Nation) and other progressive educators, Smalls’ accomplishments have been virtual wiped from America’s history books. Teachers and activists purposely ignore Smalls achievements, such as his Congressional tenure and become a Major General in the National Guard, to further their agenda of transforming America. It is up to us, Liberty, to give him and others the honor and respect they deserve and the liberal left refuse to grant them.

Smalls died a free man on the plantation where he was born a slave in Beaufort on February 22, 1915. He was laid to rest at the Tabernacle Baptist Church where a monument in his honor displays a statement he made in the state legislature in 1895:

"My race needs no special defense, for the past history of them in this country proves them to be the equal of any people anywhere. All they need is an equal chance in the battle of life."

Regardless of the ups and downs in Smalls life, he continued to put his trust in God and live according to his faith. A compassionate and forgiving man, he even took in the widow of his former master after she developed dementia and began wandering into their home. Liberty, when times get hard and situations get frustrating, take encouragement from people like Robert Smalls, who displayed the true example of human forgiveness.

That’s my 2 cents.

Love,

Mom

FROM HOUSE SLAVE TO HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

"A gold medal was presented to Mr. Smalls on behalf of the colored people of the city by Mr. J. J. Zuille, in a presentation speech, in which he expressed his doubt if there was a rebel in Charleston, who would have had even the presumption to undertake or the courage to execute such an act as his people has assembled to honor Robert Smalls for accomplishing.

"The medal is of gold, and bears a representation of the steamer Planter leaving Charleston harbor, when near Sumter. The federal fleet is seen in the distance. On the reverse it bears this inscription:

'Presented to Robert Smalls by the colored citizens of New York, October 2, 1862, as a token of their regard for his heroism, his love of liberty and his patriotism.'”