While in Beaufort, South Carolina, Mitchel contracted yellow fever and died on October 30, 1862. He was originally buried in the Episcopal Church graveyard in the town, but later moved to Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York, where he was laid to rest next to his wife in the Mitchel family plot.

Following the Civil War, the observatory appointed Cleveland Abbe as directory. Using Mitchel's telescope, Abbe began predicting the daily weather and storms. Washington D.C. soon took notice, summoning Abbe to the nation's capital where he founded the National Weather Service.

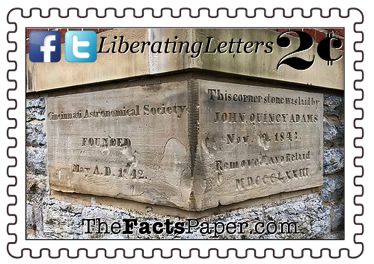

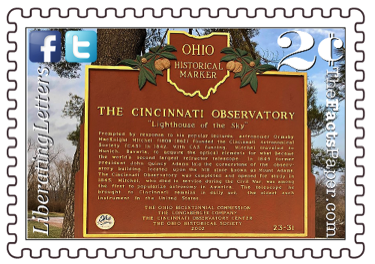

As Cincinnati grew, so did the air pollution which interfered with astronomical observation. (see How The North Was Won) Controlled by the University of Cincinnati in 1871, it was decided to move the observatory further away from downtown. Now located on Mount Lookout, the new observatory, which contains the original cornerstone laid by Adams and Mitchel, opened in 1873. A second structure was built on Mount Lookout in the early 1900s appropriately called the O.M. Mitchel Building which houses Mitchel’s telescope with a larger telescope replacing it in the original building. You can still gaze at the stars and "The Mountains of Mitchel" on Mars through it, which is the oldest in the world open to the general public.

November 9, 2019

Dear Liberty,

Ormsby looked over the crowd as the rain began to fall. This was a life-long dream for him. Would it be overshadowed by the early November weather? He noticed his speaker settling in a coach to ascend the hill. At least the dedication would occur, even if no one saw it.

As the coach climbed the muddy road, a mile-long cavalcade of spectators hiding under umbrellas followed in their Sunday best. Upon reaching the top, the speaker took his position as the spectators gathered around. The rains poured, yet nothing could drown the excitement of the day. History was being made and all wanted to be a part of it.

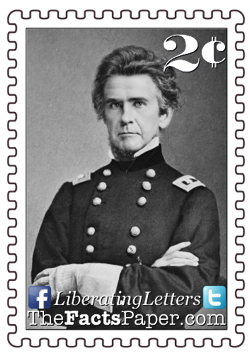

The story begins in Morganfield, Kentucky, on July 28, 1809, with the birth of Ormsby MacKnight Mitchel, though some record it as August 28, 1810. Following his father's death in 1814, Mitchel’s mother took her children north to Ohio, settling in Lebanon. He was able to attend school as his older siblings helped support the family, yet at age 12, Mitchel himself needed to leave his formal instruction to obtain a job. However, he never stopped learning as he continued to educate himself.

Locals took notice of Mitchel’s work ethic prompting the town's Postmaster General to sponsor an appointment to West Point. (see Like Father, Like Son) At the tender age of 15, Mitchel left Ohio for the United States Military Academy with just a quarter in his pocket, where he was a classmate of future Confederate Generals Joseph E. Johnston and Robert E. Lee and a year behind Jefferson Davis. Graduating 15th out of 46 in 1829, Mitchel spent two years teaching mathematics at the academy before heading to Florida as a second lieutenant of artillery. Shortly before leaving, he married a young widow of another West Point graduate, Mrs. Louisa Clark Trask.

Cincinnati called Mitchel home in 1833 where he practiced law for a year before pursuing a greater passion: teaching. Accepting a position at Cincinnati College (precursor of University of Cincinnati) in 1834, Mitchel instructed students in mathematics, natural philosophy, and astronomy. For two years, he simultaneously worked as the Chief Engineer for the Little Miami Railroad during years of its construction.

Professor Mitchel's lectures on the stars and space were so fascinating, he was asked to present a three-part series to the public. A devout Christian, he embraced that science complements God, stating, “I have absolute confidence in the wisdom and goodness of God.” Overcome with the excitement and attention of his audience for the stars, Mitchel spontaneously pledged a five-year commitment to build an observatory in Cincinnati.

A few observatories existed in the East, yet their telescopes were all small. Former presidents Thomas Jefferson, James Monroe, and John Quincy Adams all attempted to start a National Observatory, yet none succeeded. His pledge was no small feat.

Despite not having any money, Mitchel was bound to fulfill his promise. Finding a few other like-minded citizens, Mitchel helped form the Cincinnati Astronomical Society in 1842 with Judge Jacob Burnet serving as president. Mitchel committed to serving as the observatory’s director without pay for the first ten years. A $25 membership to the society, which Mitchel sold door-to-door, not only raised money for a telescope, it granted the member the right to use it. Three hundred of the city's wealthiest people down to its hardest blue-collar workers eagerly purchased memberships within three weeks, accumulating roughly $6,500 for the telescope (just over $203,000 in today's value).

Mitchel traveled to Europe where he found a $9,000 12-inch refractor lens and contracted George Metz and Joseph Mahler of Munich to construct the telescope for it. However, he needed permission from the society and more money before signing the official agreement. Once back in Cincinnati, Mitchel received the proper approval and funds in mid-November, finalizing the deal with Metz and Mahler upon sending them the money. Despite the telescope taking two years to build and deliver to Cincinnati, Mitchel had no time to breath as he still needed to secure a home for it.

Searching for the perfect location for the new telescope, he set his sights on land owned by local businessman and winemaker, Nicholas Longworth. The tallest point in the city, Longworth covered Mount Ida with grape vines for his winery. However, unable to refuse Mitchel's passion and the opportunity for Cincinnati, he donated 4 acres of his land to the project.

Having spent all the money he raised for the telescope, Mitchel now faced financing the actual observatory. Earning just $1,5oo a year as a professor, just under $47,000 in today’s value, Mitchel could not fund it himself. Therefore he started making arrangements for another fundraiser. He would organize a dedication of the observatory which he would sell tickets. However, he needed the perfect speaker to deliver remarks and lay the cornerstone. There was only one man Mitchel knew of whose passion for the project would be as great as his: former President John Quincy Adams. Adams tried multiple times to get an observatory built, which he called “Lighthouses of the Sky,” including addressing it in his “first presidential message.” His labors bore no fruit until now.

After losing his bid for re-election in 1828 to Democrat Andrew Jackson, Adams continued to serve the American people as a member of the House of Representatives. (see History Rhymes Again) Mitchel met Adams in Washington D.C. while on his way to Europe to procure a telescope. Discovering he would be in Niagara Falls for several events and appearances, Mitchel organized with Burnet to travel there and invite Adams to speak at the dedication. Mitchel approached Adams at the Cataract House, refusing to leave the former president's side until he accepted the official invitation from Burnet to speak. Adams was aquatinted with Burnet as his father, President John Adams, appointed him to the Legislative Council of the Northwest Territory and found himself wrapped up in Mitchel’s enthusiasm and consented to his invitation. (see Charting A New Course)

As dawn broke on the chilly morning of November 9, 1843, Adams refined his remarks by candlelight in his hotel room. Despite being urged by his family not to make the two-week-long 1000-mile trip from Boston, which included travel by train, stagecoach, steamship, and canal boat, the 76-year-old gave his word and was not going to miss this historical dedication. (see Locking In Our Future) It was a dream come true for him, too. Multiple stops in towns to meet people left Adams with flu-like symptoms, though he loved their affection for him. Crowds were already forming and Adams was not prepared to disappoint.

Participants in the procession found their spots as spectators lined the route. Multiple military groups and the 700 members of the Cincinnati Astronomical Society preceded the carriage carrying Adams, Mitchel, and Burnet, followed by various other organizations including the Chamber of Commerce members. With everyone in place, a sudden downpour accompanied the order to march yet the parade went on. Slipping and sloshing through the mud, ticket-holders for the speech arrived at the top of Mount Ida ready to hear Adams’ words as the military units filled the spaces on the side of the small stage.

Quickly delivering his remarks, the rain disfigured the words Adams was so carefully constructing just hours before. Upon finishing his address, Mitchel escorted Adams to the spot where the two men laid the cornerstone for the observatory. The following day, Adams stood in Wesley Chapel, the same place Mitchel vowed to build the observatory, to deliver a two-hour oration. After he concluded and the cheers of the crowd died down, it was unanimously decided to rename Mount Ida as Mount Adams, which still bears that name today. Unbeknownst at the time, Adams’ oration would be the last public speech he would deliver.

Completely depleted of funds, Mitchel managed to raise a few more donations for the society for the construction of the observatory while using his own money to cover what costs he could. In addition, Mitchel offered shares in the Society for donated time and labor of which the majority of workers agreed to. The telescope arrived in January of 1845 and was functional on April 14. Two months later the building was complete with the telescope in place.

Sometimes referred to as "The Father of American Astronomy,” Mitchel continued with his agreement to serve as director without pay even after Cincinnati College burnt down and he lost his job. Needing to provide for his family, he accepted an offer at another observatory, settling in New York, and eventually helped establish others.

When the Civil War broke out, Mitchel gave speeches in Cincinnati to help recruit for the Union Army. A man of his word, the 50-year-old felt an obligation to his vows at West Point. On August 8, 1861, Mitchel received a commission for brigadier-general and his wife, Louise, passed just 13 days later. After her funeral, he returned to Cincinnati to run the Department of the Ohio for a few months before taking command of a division in the Army of the Ohio.

Among his military accomplishments were capturing Nashville, Tennessee, and organizing a raid to disrupt the train lines in the South, which started on April 12, 1862. Despite the failure of Andrew’s Raid, “The Great Locomotive Chase” has been forever immortalized in the Buster Keaton silent movie, The General, and a Disney’s 1956 movie, The Great Locomotive Chase. Raiders who had been captured, tortured, and some executed, became the first Medal of Honor recipients.

REACHING FOR

THE STARS

When the Union Army liberated the Sea Islands off of South Carolina, white citizens fled. The Port Royal Experiment developed to help the abandoned 10,000 slaves become self-sufficient. An abolitionist, Mitchel and his family attended the church of Lyman Beecher, the father of Harriet Beecher Stowe. (see Is God Dead?) He expanded the experiment, freeing the slaves from Hilton Head and other surrounding islands with a military order. They were given land, wages, voting rights, and other freedoms. Following the war, freedmen created their first town “Mitchelville,” a self-governing town of freed slaves, located on Hilton Head Island. As was custom, several of the freed families also adopted Mitchel as their surname out of respect and honor for the man who liberated them. Following Republican President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, Democrat President Andrew Johnson not only terminated the Port Royal Experiment, he gave the land the freed slaves had been working for years back to the previous white owners. (see Civility War Ends and Views And Vetoes)

A Catholic Church and monastery now resides on the original location of the observatory. Stairs lead from the bottom of Mount Adams up to the church. A long Cincinnati tradition occurs on Good Friday as believers climb the steps, stopping to say a prayer on each one, reflect on the sacrifice of our Lord and Savior, and rejoice in the Good New of Jesus Christ.

The City of Cincinnati honors Mitchel not only with the Mitchel building but with an avenue in the downtown area. Across the river, the town of Fort Mitchell still bears its name from the Union officer, starting as one of 23 Civil War forts in Northern Kentucky.

Liberty, at a time when the nation was still growing and forming westward, one man set his sights on the stars. Cincinnati was the first major city established west of the Appalachian Mountains following the Revolutionary War and helped bring America into the 19th Century. (see The Man Who Refused To Be King and How The North Was Won) With a Cincinnati College professor studying the moon and 100 years later a future University of Cincinnati professor, Neil Armstrong, walking on the moon, the city is appropriately named the "Birthplace of American Astronomy." (see Man On The Moon) However, many at Mitchel's time still believed that science and the Bible were mutually exclusive. Mitchel, a devout Christian, looked at the study of the stars as proof of God, not in opposition to. He believed:

“An independent spirit, and a steady, honest conduct, with what capacity God has given me have carried me successfully through the world.”

Never let anyone constrain you, Liberty, to convince you that God hasn't blessed you with many talents. Don't be afraid to try different things, as Mitchel did, as you find the place God needs you. Keep your focus on God, your morals and principles rooted, and your work ethic strong. With that combination, the things you will achieve can be out of this world.

That’s my 2 cents.

Love,

Mom