The Boston Massacre was just one of a number of events occurring over a decade that resulted in the American Revolution. Yet all the while, Americans such as Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and John Adams tried to negotiate with Parliament. (see The Forgotten Battle) However, the colonists knew all discussion was over when the British landed in Boston in 1775 with two specific goals: to capture Samuel Adams and John Hancock, and to confiscate the colonists’ armory. (see Give Me Liberty) The British wanted to disarm the Patriots to prevent an uprising. (see The Shot Heard ‘Round The World) However, with Red Coats willing to fire on British subjects, as the colonists still were, the Americans realized it was time for complete independence.

Liberty, unfortunately we are again in the similar toxic atmosphere of March 5, 1770. The Boston Massacre is more than that night, it’s also the culmination of incidents leading up to it. There was the oppressive government’s laws and taxation without representation, the death of Christopher Snider, and the brawls between soldiers and colonists. With each event, both sides were using media sources to shape people’s opinions. Each development only added to the powder keg that became the Boston Massacre. And it all mirrors what is happening in America today.

Politicians continue to promise to work for the people, only to ignore their wishes, resulting in not representing their voters once in office. Black Lives Matter, Antifa, white supremacists and neo-Nazis riot and participate in unbridled violence while confronting police in efforts to provoke them into firing. (see There’s Nothing Right About The Alt-Right and Just The Facts, Ma'am) The deaths of children are being politicized for no other reason than control and many in Congress and the media, just like the British in 1775, are coming for our guns even if they won’t admit it. (see Gun Control: The First Steps Of Tyranny)

Today, the left and right are still using the media to push their propaganda and agendas. However, true American Patriots continue not to be interested in the rhetoric. They just want simple, honest justice and then to just be left alone. Yet, the powder keg is growing. If we continue to ignore the warning signs of history, we can only expect an event much worse than the Boston Massacre.

That’s my 2 cents.

Love,

Mom

John Adams sought and was granted separate trials for Preston and the soldiers as he planned to use different defenses. During Preston’s trial, no one could unequivocally say that he ordered the soldiers to fire. Combined with witness testimony of Preston raising gun barrels, the jury acquitted him based on “reasonable doubt, ” a phrase never before used. Nevertheless, it removed the soldiers’ justification of following orders. Therefore, Adams presented a case of self-defense. While his cousin Samuel Adams was portraying Attucks as a martyr to the public, John presented Attucks as an agitator and aggressor to the jury. However, the prosecution was painting the same picture of the soldiers.

Several Bostonians testified of British soldiers openly expressing their hostility towards the colonists, with one stating defendant Private Kilroy declared, "If I ever get the chance, I'll kill as many of these colonists as I can, and that he had wanted to have an opportunity ever since he landed.” Several claimed many British troops decided to provoke citizens on the evening of March 5th to force an incident allowing them to fire upon the colonists. The defense presented Henry Knox, who testified the mob shouted, “Fire, damn your blood, fire!” (see The Bookstore General) Therefore, in the chaos, it is reasonable to conclude the soldiers heard the calls for “fire,” possibly believing it was from Preston, as they felt threatened by the mob.

During closing arguments, Adams reminded the jury, “Facts are stubborn things.” If the evidence suggested the soldiers were in danger, they had to acquit. As a result, six soldiers were cleared with only two being convicted of manslaughter. The jury found Hugh Montgomery, who struggled with and shot Crispus Attucks, guilty. In 1949, it was discovered that he had confessed to his lawyers to firing the first shot. Matthew Kilroy’s participation in the brawls at Gray’s ropewalk as well as his aggressive statements, led the jury to convict him also. Claiming ‘benefit of clergy,’ or exemption from civil court for being ministers, the men escaped the death penalty, receiving the letter ‘M’ branded on their thumb before being released.

Ironically, on the same day as the massacre, Parliament discussed repealing the very laws at the heart of the rebellion. (see Acts Of Oppression) In April, all but the Tea Tax was rescinded, which was left intact specifically to remind the colonists that Parliament still reserved the right to tax them at will. (see Tyrants And Tea Parties)

The Sons of Liberty used the events of March 5th to spread the message of Britain’s oppression and rally Patriots. Labeled the Boston Massacre during the Civil War, abolitionists also used it and Attucks’ fight for liberty to rally against the oppression of slavery. Following the trials, much of the efforts to keep the anger going failed as Bostonians and others realized the mob was as much to blame as the Red Coats. They wanted change, but not through unharnessed violent means. Loyalists used the event to paint the colonists as unsophisticated, uncivilized creatures needing the guidance of the crown. Regardless, just like with the riots immediately following the Stamp Act, Americans rejected unbridled disorder as well as mob rule mentality. (see Tree Of Liberty) Instead, they sought honest justice, which resorted to violence only if absolutely necessary.

March 5, 2018

Dear Liberty,

A crowd started gathering on King Street as a young apprentice, Edward Garrick, argued with Private Hugh White. Garrick began poking White in the chest with his finger, resulting in the sentry stepping off his post at the Custom House. As the altercation escalated, White struck Garrick on the head with the butt of his musket. Garrick howled in agony as his friend Bartholomew Broaders stepped into the fight. Local bookstore owner, 19-year-0ld Henry Knox, ran up to White and reminded him that firing upon civilians without orders would mean his death. (see The Bookstore General)

In the growing chaos, the church bells rang indicating a fire. More people flooded the streets in efforts to assist, only to find a riot brewing. The crowd converged on White, who had returned to the Custom House steps. Feeling endangered, White sent runners to alert Captain Thomas Preston for help. Bayonets at the ready, Preston arrived with seven soldiers, who had to force their way through the crowd to reach White. Upon their arrival, many of the reasonable citizens left the area.

Of those that remained, Crispus Attucks began leading the crowd. A sailor, Attucks was very familiar with the British practice of impressing American sailors into the British Navy, and he resented it. The mob taunted the soldiers, throwing snowballs, chunks of ice, oyster shells, rocks, mud and the like at them while brandishing sticks and clubs. Backs against the wall and completely surrounded, the Red Coats held tight even as the rioters began to spit on and hit them with their weapons. Knox again entreated Preston not to fire, who understood he could not legally do so without reading the Riot Act first. (see Reading The Riot Act) Not only did Preston know this, so did the mob.

“Come on you rascals, you bloody scoundrels, you lobsterbacks, fire if you dare, we know you dare not.” “Be not afraid; they dare not fire: why do you hesitate, why do you not kill them, why not crush them at once?” In the confusion, Private Hugh Montgomery was hit with a club and knocked to the ground. Attucks struggled with Montgomery, trying to wrestle away his gun. “Fire! Why don’t you fire??” As he rose, Montgomery discharged his weapon, hitting Attucks in the chest, killing him instantly. From somewhere in the crowd, another call for “Fire” is heard. The mayhem turned more deadly as several other soldiers fired their weapons.

Preston began pushing the gun barrels in the air to avoid their blasts hitting the people. As the smoke cleared, three Bostonians lay dead on King Street, two critically shot, with six more wounded. Many in the crowd dispersed as Preston tried to gain order. However, fearing a lynch mob, Governor Thomas Hutchinson appeared in the Custom House balcony and declared the soldiers would be tried for the incident, ending the night’s ordeal. (see Tyrants And Tea Parties)

It was never determined if the calls for fire were from Montgomery asking for assistance in his struggle with Attucks, from other soldiers, from the protestors, or from a civilian still thinking the church bells were announcing a fire in the town. Regardless, it was only a matter of time before this powder keg exploded.

Patriots organized and began resisting British taxation following The Stamp Act of 1765, resulting in the Liberty Tree and the Sons of Liberty. (see Tree Of Liberty) Parliament repealed the Act in 1766 but replaced it with several Townshend Acts in 1768, leading to boycotts and smuggling. (see Acts Of Oppression) British soldiers were dispatched to Boston to control the citizens following the Liberty Riot caused by the seizure of John Hancock’s sloop Liberty.

The soldiers, who were loyal to the crown, viewed the colonists as traitors to the monarchy. Therefore, they mocked, berated and insulted them. In addition, soldiers were poorly paid and often sought supplemental wages from additional employment. On the other hand, colonists felt oppressed, abused and ignored by the king and Parliament. The occupying soldiers only re-enforced their feelings of suppression, deepening their resentment towards the crown. To top it off, the soldiers took precious jobs of which the colonists needed to survive.

Loyalist merchants often refused to participate in the boycotts. On February 22, 1770, an effigy was placed in front of one such store. Confidential customs informant, Ebenezer Richardson, tried to remove it before returning to his nearby home. Involving several local citizens in a heated argument, insults flew from Richardson, his wife, and the others, as a crowd gathered, including several boys. They began throwing snowballs and then rocks to force the Richardsons inside, where Richardson retrieved his gun and shot randomly into the crowd from his window. One adult received a non-life-threatening wound, but 1o-year-old Christopher Snider (or Seider) was killed. (see First Blood and Defining The American Spirit) Samuel Adams promoted his death as the result of British tyranny, walking his large funeral procession passed the Liberty Tree. (see Tree Of Liberty)

Tired of the rebellion, Red Coats began looking for a reason to confront the colonists. Wanting retaliation, citizens also began instigating confrontations. British were under strict orders not to use force against the citizens, who knew it and therefore, did not hold back in their attacks. Both sides were itching for a fight, and they began to scratch just a little over a week later on March 2nd.

While out to gather water, Private Patrick Walker passed by John Gray’s ropewalk. Gray employee William Green asked if he was looking for a job, and he said, “Yes”. Green responded with a degrading joke. A brawl ensued, where Walker left defeated. He returned twice, each time with more soldiers, only to be bested by the colonists both times. The soldiers wanted revenge. This was the atmosphere that permeated the Boston air that fateful day of March 5th.

By the end of the month, Captain Preston and the eight soldiers were indicted for the murders of five men. Crispus Attucks, a mulatto runaway slave, became known and revered as the first casualty of the American Revolution. Samuel Gray, a Gray’s ropewalk employee, was shot while trying to stop the British from firing. Sailor James Caldwell was struck down while fleeing. After taunting the British to fire, 17-year-old Samuel Maverick ran after the shooting began and made it to his mother’s home before dying hours later. Patrick Carr was in the streets responding to the church bells. He died on the 14th, yet supposedly on his deathbed absolved the soldiers, stating they were provoked.

The prosecution was led by Loyalist Samuel Quincy. Several Loyalist attorneys rejected the defendants' case before Sampson Salter Blowers, a former law student of Gov. Hutchinson, consented to serve on the counsel. A Sons of Liberty co-founder and Samuel’s brother, Josiah Quincy Jr., also joined the team. Robert Auchmuty Jr. agreed, but only if John Adams was the co-counsel. Presented with the case, Adams desired to see true justice and not mob rule. He accepted the job.

The Red Coats sat in jail for nine months while John Adams, Samuel Quincy and Hutchinson prolonged the trial to allow cooler heads to prevail. However, it did allow Samuel Adams and the Sons of Liberty, as well as Loyalists, time to use the incident for political advantage. Knowing the pen is mightier than the sword, both sides took to the written word to spread their perspective of the recent events as well as shape opinions.

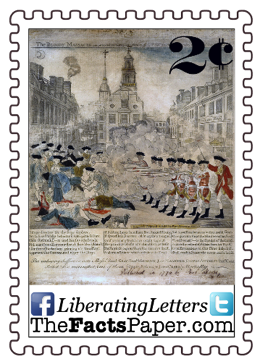

MAYHEM AND MASSACRES

The day after the shooting, Samuel Adams was chosen to begin petitioning for the removal of all troops. Henry Pelham designed an image portraying the event, made famous by Paul Revere’s slightly modified version. (see The Forgotten Black Founding Father, The Shot Heard 'Round The World, Defining The American Spirit, and Tree Of Liberty) Dubbing it “The Bloody Massacre,” Revere used the term to magnify its impact. Multiple pamphlets and writings sent to other colonies as well as London depicted the soldiers as eager participants in colonial harassment. Likewise, Hutchinson distributed depositions of soldiers characterizing the Bostonians as selfish and unwilling to accept Parliament’s laws. They claimed anarchy and unruliness preceded what could have only been an ambush of the soldiers. Therefore, for the safety of both the soldiers and the citizens, all regiments were removed to Castle Island by May.